Novel cancer vaccine offers new hope for dogs — and those who love them

A Yale researcher developed a vaccine that can slow or halt certain cancers in dogs. And it could be used to treat humans in the future.

By Mallory Locklear march 5, 2024

During a sunny morning on Florida’s Gulf Coast last month, an 11-year-old golden retriever named Hunter bounded through a pine grove. Snatching his favorite toy, a well-chewed tennis ball attached to a short rope, he rolled through the tall grass, with an energy that seemed inexhaustible. A passerby might not have even noticed that this playful golden has only three legs.

For Deana Hudgins, the dog’s owner, it seems almost unthinkable that two years ago Hunter was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a form of bone cancer that kills upwards of 65% of the dogs it afflicts within 12 months, in his left front leg.

For many years Hunter worked alongside his owner as a search-and-rescue dog, helping find victims of building collapses and other disasters. He no longer performs those duties, but does still help Hudgins train other dogs. The energetic golden can also run, fetch, and catch as well as ever.

And two years since his initial diagnosis, Hunter has no signs of cancer. The dog’s life-saving treatment incorporated typical approaches, including amputation of the left leg and chemotherapy. But Hunter also received a novel therapy — a cancer vaccine developed by Yale’s Mark Mamula.

If we can provide some benefit, some relief — a pain-free life — that is the best outcome that we could ever have.”

The treatment, a form of immunotherapy that is currently under review by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which regulates animal treatments, has been subject to multiple clinical trials over the past eight years. And the results are promising; for hundreds of dogs, including Hunter, the vaccine has proved effective.

Mamula, a professor of medicine (rheumatology) at Yale School of Medicine, believes the vaccine offers a badly needed weapon in the fight against canine cancer.

“Dogs, just like humans, get cancer spontaneously; they grow and metastasize and mutate, just like human cancers do,” said Mamula. “My own dog died of an inoperable cancer about 11 years ago. Dogs just like humans suffer greatly from their cancers.

“If we can provide some benefit, some relief — a pain-free life — that is the best outcome that we could ever have.”

Even as recently as a decade ago, Mamula didn’t anticipate that he would one day develop a cancer vaccine for dogs. A rheumatology researcher, he studies autoimmune diseases like lupus and Type 1 diabetes and how the body gives rise to them.

But that work eventually led him to cancer research as well.

Autoimmune diseases, Mamula says, are characterized by the immune system attacking the body’s own tissues; in the case of Type 1 diabetes, the immune system targets cells in the pancreas.

Then several years ago, using what they knew about autoimmunity, Mamula and his research team developed a potential cancer treatment that they say initiates a targeted immune response against tumors.

“In many ways tumors are like the targets of autoimmune diseases,” he said. “Cancer cells are your own tissue and are attacked by the immune system. The difference is we want the immune system to attack a tumor.”

It was a chance meeting with a veterinary oncologist soon thereafter that made Mamula think that this novel treatment might work well in dogs.

Targeting tumors

There are about 90 million dogs, living in 65 million households, in the United States alone. Around one in four dogs will get cancer. Among dogs 10 years or older, that ratio jumps to around one in two.

Yet the therapies used to treat these cancers remain fairly antiquated, Mamula says.

“There have been very few new canine cancer treatments developed in decades — it’s a field that is begging for improvement,” he said.

In 2015, Mamula met a veterinary oncologist named Gerry Post. During his 35-year career Post has treated cancer in snakes, turtles, and zoo animals. But most of his patients are dogs and cats.

Through conversations with Post, Mamula realized that it wouldn’t be difficult to make the leap from human to dog cancers. Together they would launch an early-phase study into Mamula’s dog cancer vaccine.

“Dog and human cancers are quite similar in a number of ways,” said Post, chief medical officer of One Health Company, a canine cancer treatment group, and an adjunct professor of comparative medicine at Yale School of Medicine. “Whether it’s how the cancers appear under the microscope, how the cancers behave, respond to chemotherapy, develop resistance, and metastasize.”

After talking with a veterinary oncologist, Mamula realized that it wouldn’t be difficult to make the leap from addressing human cancers to dog cancers.

Even the types of cancers that afflict dogs and humans are similar. Like humans, dogs can get melanoma, breast cancer, colon cancer, and osteosarcoma, among others.

When it comes to curing these diseases, these similarities bring an important benefit: understanding cancer in one species will help scientists understand cancer in the other. And treatments that work well for one may actually work well for both.

Several types of cancers in both humans and dogs have been found to overexpress proteins known as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). These include colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and osteosarcoma. One type of treatment currently given to human patients with these cancers involves monoclonal antibodies, proteins that can bind to and affect the function of EGFR and/or HER2. However, patients can develop a resistance to them and their effects wane over time.

For their treatment, Mamula and his team wanted to take a different approach.

Monoclonal antibody treatments are produced from one immune cell and bind to one part of the EGFR/HER2 molecules, but Mamula and his team wanted to induce a polyclonal response.

Doing so, he says, would create antibodies from multiple immune cells, rather than just one, which could bind to multiple parts of the EGFR/HER2 molecules instead of a single area. This would, in theory, reduce the likelihood of developing resistance.

The research team, led by Hester Doyle and Renelle Gee, who are both members of Mamula’s Yale lab, with assistance from the New Haven-based biotechnology company L2 Diagnostics, LLC, tested many different candidates in order to find just the right compound. They eventually found one.

After first testing it in mice, and finding promising results, they initiated their first clinical trial in dogs in 2016.

‘I was willing to try whatever I could’

Deana Hudgins knew there was something special about Hunter before she brought him home as an 8-week-old puppy, back in 2012, and began training him to be her next search-and-rescue partner.

The smallest of 18 puppies from two litters, Hunter wasn’t the obvious choice when she began looking for a partner.

“He was the runt,” said Hudgins, who has been training search-and-rescue dogs since 2001 and now runs her own company, the Center for Forensic Training and Education, which provides canine training in Ohio and Florida. “But in his case, it made him a little scrappy. He was small but very confident and very brave.

“When all of the other puppies were sleeping at the end of the day, he was still running around, climbing all of the toys, retrieving things. We need confident puppies, and that’s what he possessed.”

By the time he was a year old, Hunter began aiding searches at sites across the United States, working with local law enforcement and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), following natural disasters. His first search, in 2014, was at the site of a mudslide in Oso, Washington that killed 43 people. In his final FEMA search, he helped search for victims of the devastating condominium collapse in the Miami suburb of Surfside, Florida, in June 2021. Hunter was involved in hundreds of searches in the years between.

In 2022, Hunter was still very active — and had just earned another service certification — when Hudgins noticed that he seemed uncharacteristically sore following a five-day training class.

“I’ve always been very proactive with my dogs because I spend every day with them, and so I notice very little things,” she said. “And he’s not a dog to limp.”

A veterinarian assumed that Hunter had strained something, suggesting anti-inflammatories, but Hudgins insisted on an x-ray. The test revealed the osteosarcoma in Hunter’s leg.

After doing a lot of research, and consulting with different veterinary groups about what steps to take, Hudgins decided that amputation offered the best chance for Hunter’s survival, along with chemotherapy.

But during that research, Hudgins had also come across Mamula’s vaccine trial. So she reached out to a colleague, James Hatch, a former Navy SEAL who trained dogs in the military and whose nonprofit supports service dogs. Hudgins knew that Hatch also happened to be at Yale, where he is a student in the Eli Whitney Students Program.

“I was willing to try whatever I could to keep [Hunter] around as long as possible,” said Hudgins. “We ask a lot of our working dogs. They work in environments that are very dangerous and often deadly. And my promise to all of them is I will do whatever I have to do to give them the best, healthiest, longest life possible. Dogs don’t survive this disease so there was no downside to me for trying the vaccine.”

Hatch connected her with Mamula, and soon Hunter was part of the clinical trial. He received his first vaccine dose ahead of his amputation surgery, his second before initiating chemotherapy, and a booster last summer.

Twenty-two months since his cancer diagnosis, Hunter is now considered a long-term osteosarcoma survivor and Hudgins says he’s thriving.

“He adjusted very well to his front limb amputation,” she said. “He continues to run around the yard. He swims in the pool. He comes with me to training and chases the other dogs around the yard.”

During a recent morning in Florida, Hunter drifted toward a nearby pond while playing outside. Hudgins, knowing the potential risks of straying too close to a pond in Florida (“There are alligators everywhere.”), quickly called him back. Hunter immediately returned to her.

“From a very young age, Hunter wanted to learn the rules of the game,” she said. “He was eager to go to work every day. I am very, very lucky to have been able to be his partner for 10 years. Hunter is one of those once-in-a-lifetime dogs.”

‘A whole new toolbox’

Hunter’s positive response to the treatment is one many other dogs have experienced as well.

To date, more than 300 dogs have been treated with the vaccine during a series of clinical trials, which are still ongoing at 10 sites in the U.S. and Canada. The findings, which have been published in a peer-reviewed study, have shown that the treatment creates antibodies that are able to home in on and bind to tumors, and then interfere with the signaling pathways responsible for tumor growth.

According to the research team, the vaccine increases the 12-month survival rates of dogs with certain cancers from about 35% to 60%. For many of the dogs, the treatment also shrinks tumors.

While future studies will determine if the vaccine can reduce the incidence of cancer in healthy dogs, the treatment for now remains a therapeutic treatment option after a cancer diagnosis has been made.

Witnessing the happiness that successful therapies provide to families with dogs is incredibly rewarding.

But even this represents something more than just “a new tool” in the fight against canine cancer, Post says. It’s a whole new toolbox.

“And in veterinary oncology, our toolbox is much smaller than that of human oncology,” he said. “This vaccine is truly revolutionary. I couldn’t be more excited to be a veterinary oncologist.”

Mamula has created a company, called TheraJan, which aims to eventually produce the vaccine. Last year, the company (whose name is inspired, in part, by the late Yale immunologist Charles Janeway, who was Mamula’s mentor) won a Faculty Innovation Award from Yale Ventures, a university initiative that supports innovation and entrepreneurship on campus and beyond.

While launching clinical tests of the vaccine’s effectiveness in humans may be a logical future step, for now Mamula is focused on getting USDA approval of the vaccine for dogs and distributed for wider use.

No matter where it goes, it’s a project close to his heart.

“I get many emails from grateful dog owners who had been told that their pets had weeks or months to live but who are now two or three years past their cancer diagnosis,” he said. “It’s a program that’s not only valuable to me as a dog lover. Witnessing the happiness that successful therapies provide to families with dogs is incredibly rewarding.”

And once the vaccine becomes available for public use, he says, for working dogs like Hunter it will always be free of charge.

media contact Fred Mamoun: fred.mamoun@yale.edu, 203-436-2643

Managed by the Office of Public Affairs & Communications

Copyright © 2024 Yale University · All rights reserved · Privacy policy · Accessibility at Yale

Ear Mites in Dogs

Not all messy ear conditions are due to mites. Learn to recognize the signs of ear mites in dogs and get appropriate treatment for your dog’s ear mite infection.

By Dr. Jennifer Bailey, DVM – Published: February 27, 2024

Are itchy, stinky ears interfering with your dog’s daily dose of fun? A quick internet search might lead you to ear mites in dogs as the culprit. You can try administering an ear mite medication in your dog’s ears to alleviate his discomfort. But before you reach for that over-the-counter ear mite medication, you should know more about ear mites in dogs, and learn when to call in a professional (in other words, your dog’s veterinarian!).

Otodectes cynotis is an ear mite that infects the ear canals of dogs, cats, rabbits, and ferrets. Although this species of ear mite prefers these three species of mammals, any mammalian species will satisfy its needs for survival. It survives by ingesting the dead skin cells and ceruminous exudate (ear wax) that line the ear canals.

Symptoms of ear mites in dogs

Ear mites in dogs cause an inflammatory reaction in their ear canals. This is what causes your dog to scratch at his ears and shake his head. The ceruminous glands that line your dog’s ear canals ramp up production of even more ear wax to drive out the ear mites. That smelly, dark brown, crumbly discharge in your dog’s ears is a combination of ear wax, ear mites, and their excrement. It often resembles the color and texture of coffee grounds.

Dogs who have ear mites will often develop a secondary bacterial and/or yeast infection in their ears. This can change the color and texture of the ear discharge from crumbly brown to creamy yellow or green. Sometimes the discharge may be mixed with blood if your dog scratches his ears so hard that they bleed.

If it becomes too crowded inside your dog’s ears, then some of the mites will leave the ear canals to find more spacious living quarters. Ear mites can live on the skin surface outside of your dog’s ears, snacking on skin oils and dead skin cells. They can be found crawling on the skin around the ears and on the neck and face. When your dog curls up in a ball to sleep, the mites can crawl out of the ears onto the skin of the rear end or tail. Mites will cause itchiness wherever they reside, so dogs with ear mites may scratch and develop skin redness and bald spots in areas besides their ears.

The only way to accurately diagnose an ear mite infestation is to examine a sample of your dog’s ear discharge under a microscope. The average length of an ear mite is only three-tenths of a millimeter. While this is too small to be seen by most people’s unaided eyes, ear mites can be easily spotted under a low-power microscope lens.

Treatment for ear mites in dogs

There are several treatments available to rid your dog of ear mites. But the only dogs who should receive treatment for ear mites are ones who have been diagnosed with ear mites or who live in a home with a pet who has been diagnosed with ear mites. Ear infections caused by bacteria, yeast, or a combination of bacteria and yeast can look similar to ear mite infestations.

It is important to know what you are treating before you treat. Using the incorrect treatment can worsen the underlying problem, cause more pain for your dog, and may lead to hearing loss or deafness. If your dog is scratching at his ears, shaking his head, and having discharge from his ears, have your dog examined by a veterinarian as soon as possible to determine the best course of treatment.

How do dogs get ear mites?

Ear mites spend their entire life cycle on one or more host animals. Ear mites can live for a few days in the environment but cannot survive without being on a host animal.

Ear mites spread by crawling between animals. They cannot hop or jump. To become infested with ear mites, a dog must have direct contact either with another animal who has ear mites or the gunk that recently came out of an infected animal’s ears.

How to prevent ear mites in dogs

Regularly use a flea or heartworm preventative that contains an ingredient shown to be effective against ear mites, such as Revolution, Advantage Multi, Interceptor, Nexgard, Bravecto, or Simparica.

If there are cats in the home who venture outside, regularly use a flea preventative on those cats that contains an ingredient shown to be effective against ear mites, such as Revolution, Advantage Multi, or Bravecto.

If there are ferrets in the home who venture outside on a harness and leash or rabbits in the home who spend time outdoors in a hutch or pen, talk to your veterinarian about applying Revolution monthly to these pets. This is an off-label use of Revolution in these species and must be prescribed and dosed correctly by your veterinarian.

Dr. Jennifer Bailey is a 2012 graduate of the Western University of Health Sciences College of Veterinary Medicine. She is an emergency and urgent care veterinarian at an emergency and specialty practice in Syracuse, New York.

Veterinarians say fears about ‘mystery’ dog illness may be overblown. Here’s why

PUBLIC HEALTH

DECEMBER 1, 20235:00 AM ET

HEARD ON MORNING EDITION By Will StoneLISTEN· 3:46

Many dog owners are worried about reports of a mysterious respiratory illness affecting dogs.

I watched anxiously as my 80-pound doodle trotted off to his regularly scheduled doggy daycare, blissfully unaware that he’d soon be swapping all manner of germs with his buddies.

I wondered, does this constitute a high-risk situation? This was the same small circle of dogs he played with every week, but I had no clue where the others spent their time.

Would he come home with more than a healthy dose of slobber? Maybe, even, a new and poorly-understood pathogen?

Reports of respiratory illness afflicting dogs have put many dog owners like myself on edge in recent weeks.

Social media is filled with increasingly distressing headlines and anecdotes of otherwise healthy pets coming down with a raft of symptoms, everything from a hacking cough to sometimes life-threatening complications.

Most concerning, veterinarians say they’re unable to identify what’s making the dogs ill and the go-to treatments for canine respiratory illness, generally called “kennel cough,” appear to be ineffective.

The list of states with suspected cases of a “mystery illness” has grown to include most regions of the country.

The uncertainty is worrying for the 65 million households with a dog — especially those whose pets have fallen sick. In rare cases, dogs have died.

But veterinarians who study infectious diseases say this may, in fact, not be an outbreak of a singular illness at all. There’s still scant evidence connecting these cases with any common pathogen, let alone to an altogether new one.

“It’s entirely possible that there are just a ton of different bugs and viruses causing disease in different parts of the country,” says Dr. Jane Sykes, a professor at UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine who focuses on infectious disease. “We just have to be a bit careful about panicking.”

Because the U.S. doesn’t have a robust surveillance system for infectious disease in dogs, it’s hard to track these cases and discern whether anecdotes and scraps of data add up to widespread and concerning patterns.

“Two things keep getting mixed up,” says Dr. Scott Weese, an infectious disease veterinarian at the Ontario Veterinary College. “Do we have more disease? And do we have something new? Because those are not necessarily connected.”

Poor clinical understanding of ‘atypical’ illness

Weese says it seems that certain parts of the country are experiencing an uptick in canine respiratory illness. However, it’s possible the deluge of media coverage and attention on social media has created the appearance of a nationwide outbreak that may not exist in reality.

“I get an email a couple of times a week saying, ‘hey, are we seeing more respiratory disease in dogs?” he says, “But I’ve been getting that email for like five years.”

Dogs often pick up viruses and bacteria from other pets when socializing or being cared for in group settings.

Despite all the attention on individual cases, there’s nothing at this point “that would indicate there’s a national outbreak, anything that would indicate these are all medically connected to each other,” says Dr. Silene St. Bernard, a regional medical director for VCA Animal Hospitals, which runs more than a thousand hospitals in the U.S. and Canada.

Of course, none of this skepticism rules out the possibility that there is a new pathogen starting to spread.

For example, researchers in New Hampshire have identified an odd bacteria that could be relevant, although they haven’t yet confirmed this is actually what’s causing illness in some dogs.

“The three choices are: There is not a new disease out there. There is a disease whose incidence is particularly high right now and it’s a known agent,” says Dr. Kurt Williams, who directs the Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, “Or there’s truly something new and novel out there.“

While there’s no official tally, there are now hundreds of cases of an “atypical canine respiratory disease,” according to state health officials and medical organizations in more than a dozen states.

However, Williams cautions this framing can give the impression that a clearly defined disease is spreading. “We have a very poor understanding of the cases clinically,” he says.

Generally speaking, the unifying symptom seems to be a persistent cough that doesn’t resolve as would be expected with typical cases of kennel cough. In the worst cases, dogs can come down with severe pneumonia, which sometimes develops rapidly.

Negative tests may not rule out known pathogens

Similar to veterinarians in other states, Dr. Melissa Beyer says she’s not seeing dogs with an unidentified illness dying in high numbers. What’s puzzling is they can’t identify the causes of their illness.

“We’ve been running respiratory panels to check about 20 different viruses and bacteria,” says Beyer, who runs South Des Moines Veterinary Center, “A lot of them are coming back negative.”

This observation by veterinarians around the country has raised the specter of a new pathogen, but there’s actually many reasons why the PCR tests used for canine respiratory illness could come back negative, says Sykes of UC Davis.

The sample collected could simply be too small, or taken from the wrong part of the body; the levels of the pathogen can change from day to day, or the dog’s body might have stopped shedding it by the time the sample was collected.

Even if it’s a well-known bug, the genetic sequence might be different enough that the PCR test fails to detect it.

“For some of these organisms, negative results are even more common than positive test results,” she says.

Sykes, who founded the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases, says the observations that dogs are resistant to standard treatment is thorny because many dogs are treated unnecessarily with antibiotics, when, in fact, they have a viral illness.

“What’s actually being said here by veterinarians in these different locations is really that dogs are taking a long time to recover,” she says.

Symptoms could be caused by a ‘pathogen soup’

Of the many possibilities, she suspects one could be a “pathogen soup,” essentially a mixture of co-occurring infections that are making dogs especially sick and prolonging their recovery.

Respiratory disease in dogs wax and wane and the last few years have seen more “dramatic swings” where outbreaks last longer and take place across broader areas, says Dr. Weese.

The epidemiology around this illness is especially hazy because there’s already some mix of the usual suspects, like Bordetella and canine respiratory coronavirus (not related to COVID-19), with outbreaks of canine flu layered on top of that.

The uptick in illness doesn’t happen in a vacuum, either: Dog ownership in the U.S has gone up steadily, vaccinations have been disrupted in recent years, and the holiday season has led more people to board their dogs or bring them on travel and mingle them with other pets.

Pathologist search for clues in the lab and in lungs

Still pathologists are keeping an open mind as they collect samples from sick dogs and search for clues.

“I do trust veterinarians,” Williams says, “If they say we are seeing increased numbers of cases and they’re behaving clinically differently than we’re used to, we need to pay attention.“

In New Hampshire, a team of researchers have used genetic sequencing to turn up evidence of what appears to be a new bacteria, similar to Mycoplasma.

While they haven’t been able to culture the bacteria, they’ve identified it in samples collected from dogs who fell ill in New Hampshire last year and from dogs in neighboring states this year.

“We think this may be a pathogen,” says David Needle, a pathologist at the New Hampshire Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, “We don’t think it itself is responsible for mortalities very often, but it may allow for secondary infections that could cause mortalities.”

Needle is analyzing samples from other states to see if they can find the same genetic material in sick dogs there.

While intriguing, Weese points out that Mycoplasma can commonly be found in dogs with and without respiratory disease. He says it’s way too soon to assume this is behind any of these outbreaks.

“We just don’t know at this point,” he says.

In Oregon, Williams is skeptical that would explain what he’s seeing in his state, saying it’s possible something distinct is happening in the Pacific Northwest.

In fact, he’s in the early stages of examining the lungs of dogs who died from the atypical respiratory illness that has sickened more than 200 dogs in Oregon. So far, he’s finding acute injury in the small air sacs, called alveoli, and bleeding from that into the lungs.

“I don’t want to get out over my skis here, but I’ve looked at a lot of dog lungs in my career, and these are a little bit different,” he says, “So it makes me think, maybe, there’s something out there.”

Sponsor Message

Take precautions but don’t succumb to fear

For now though, veterinarians tell NPR it’s wise for dog owners to take common-sense measures, like avoiding contact with sick dogs and making sure your dog is up to date on its vaccine.

Ultimately, Weese says it will depend on your situation.

“If there are a lot of sick dogs in your area, then it is reasonable to be more restrictive. If you’ve got a dog that’s at high risk for disease, be more restrictive,” he says.

Some people may want to steer clear of “high traffic” public places like dog parks and if possible, boarding facilities, groomers and other crowded settings, says Dr. Ashley Nichols, president of the Maryland Veterinary Medical Association.

“Those are the activities that if you’re nervous about exposure, I would avoid because that’s where dogs with many backgrounds, many immunization levels and things like that mix,” she says.

Nichols worries about the exponential rise in fear among some pet owners. She and her colleagues have noticed it’s led some to skip routine health care, worried their dog might catch something at the clinic.

“I understand people’s concerns. I think avoiding the vet clinic is not the way to go,” she says.

And if your pet does get sick, get them seen immediately. Ashley Dozier, a vet tech in Virginia Beach, initially wasn’t too worried when her young golden retriever started coughing earlier this fall. That changed as his condition deteriorated, though.

“I brought him in to work and he was diagnosed with pneumonia,” says Dozier. “He went a total of nine weeks on three different types of antibiotics and a round of about three to four weeks of steroids.”

Now off the steroids, she says he’s finally starting to bounce back.

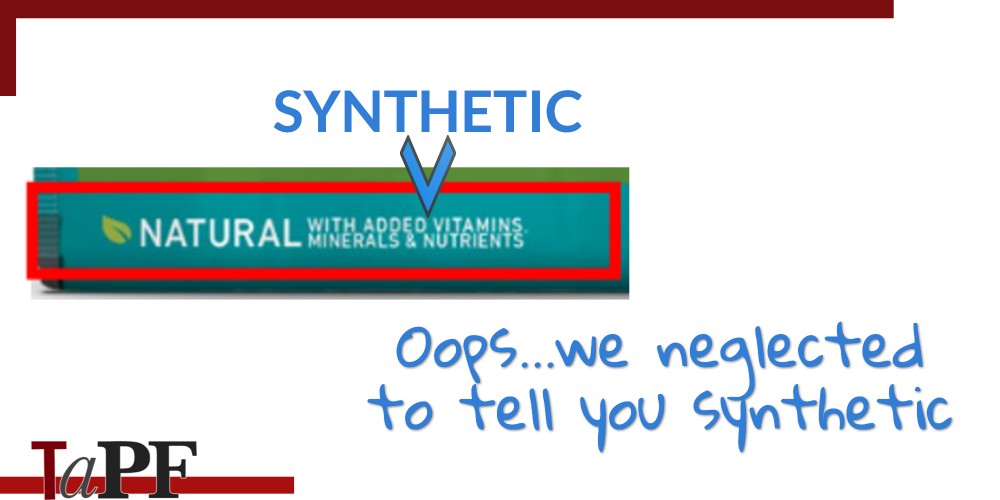

Purina Sued For Natural Claims

The lawsuit claims Purina markets their pet foods as “Natural” when they contain synthetic ingredients.

A lawsuit was recently filed against Purina Petcare Company in the state of New York. The lawsuit claims Purina markets its pet foods “in a systematically misleading manner that many of its products are natural” – when the pet foods actually contain “multiple synthetic ingredients.”

The lawsuit states: “Defendant clearly claims the Products are ‘natural’ on the Products’ label, capitalizing on the preference of health-conscious pet owners to purchase pet food that is free from synthetic ingredients.” The court documents provide this example:

The lawsuit continues: “However, Defendant’s Products contain multiple synthetic ingredients.” Examples of synthetic ingredients provided were “zinc sulfate, copper sulfate, calcium pantothenate (or D-calcium pantothenate), thiamine mononitrate, l-lysine hydrochloride, pyridoxine hydrochloride, and menadione sodium bisulfite complex.”

“As a result of its deceptive conduct, Defendant violates state consumer protection statutes and has been unjustly enriched at the expense of consumers.”

“Defendant’s labeling and advertising puts forth a straightforward, material message: the Products contain only ingredients that are natural. Reasonable consumers would understand Defendant’s labeling to mean that the Products contain only natural ingredients, and not any synthetic substances.”

“Because the labeling claim uses the word ‘and’ rather than ‘but,’ and does not specify that the added vitamins, minerals and/or nutrients are synthetic, a reasonable consumer would expect that the ‘added vitamins, minerals and nutrients’ are natural as well.”

Do you agree? Does Purina’s label claim – “Natural Cat Food with added vitamins, minerals & nutrients” transparently tell consumers this pet food contains un-natural (synthetic) ingredients? Or is the statement misleading?

For more information on this lawsuit pet owners can contact the law firm listed on the court documents:

BURSOR & FISHER, P.A.

Joshua D. Arisohn

Julian C. Diamond

1330 Avenue of the Americas, 32nd Fl.

New York, NY 10019

Telephone: (646) 837-7150

Wishing you and your pet(s) the best,

Susan Thixton

Pet Food Safety Advocate

Author Buyer Beware, Co-Author Dinner PAWsible

TruthaboutPetFood.com

Association for Truth in Pet Food

Become a member of our pet food consumer Association. Association for Truth in Pet Food is a a stakeholder organization representing the voice of pet food consumers at AAFCO and with FDA. Your membership helps representatives attend meetings and voice consumer concerns with regulatory authorities. Click Here to learn more.

What’s in Your Pet’s Food?

Is your dog or cat eating risk ingredients? Chinese imports? Petsumer Report tells the ‘rest of the story’ on over 5,000 cat foods, dog foods, and pet treats. 30 Day Satisfaction Guarantee. Click Here to preview Petsumer Report. www.PetsumerReport.com

Find Healthy Pet Foods in Your Area Click Here

The 2023 List

Susan’s List of trusted pet foods. Click Here to learn more.

The 2023 Treat List

Susan’s List of trusted pet treat manufacturers. Click Here to learn more.

Learn More

Plants safe for dogs and cats

Learn about pet-friendly plants and flowers to help brighten up your home, yard, and garden with these beautiful blooms.

Written by Shannon Perry & Alex Hunt

— Medically reviewed by Dr. Erica Irish

Updated October 13, 2023 From: Betterpet.com at https://betterpet.com/plants-safe-for-dogs/

Table of Contents

- Safe plants for dogs and cats

- Precautions about pets and plants

- Unsafe plants for dogs

- If your dog ingests a potentially deadly plant

- Plant poison prevention

- Frequently asked questions

The essentials

- Many common plants are toxic to pets — Most will only have mild effects if ingested, but a few, including daylilies and sago palms, can result in death.

- You can have a green thumb AND be a pet parent — The list of non-toxic plants safe for dogs and cats is long, too! Keep our lists — and the ASPCA’s database — handy when shopping at the nursery.

- Obsessive plant eating is cause for concern — Call your veterinarian if you notice your dog is eating grass more frequently than normal or has signs of stomach discomfort.

Pets love to sniff — and sometimes taste — what’s around them. The good news is that having dogs and cats doesn’t mean giving up a beautiful home and garden. If it’s time to spruce up your house or apartment, garden, balcony, or raised beds, this list of pet-safe plants, shrubs, and garden greenery will add pops of color and freshness while keeping your furry friends safe.

When shopping at the nursery or if you use a landscaper for your garden, make sure to mention the fact that you have pets. Most garden centers will make recommendations and help you find different varieties of pet-safe greenery and flowers for your home and yard.

Ultimate list of plants that are safe for dogs and cats

While the ASPCA warns that any ingested plant material may cause gastrointestinal upset for dogs or cats, it considers the below plants to be non-toxic. These are also among the most popular indoor plants, as defined by home-improvement giant Home Depot and #PlantTok and #plantfluencer life.

african violet

areca palm

boston fern (sword fern)

bottlebrush

camellia

canna lilies

cast iron plant

chinese money plant

crepe myrtle

echeveria

forsythia

fuchsias

common lilac

magnolia bushes

nasturtium (indian cress)

nerve plant

oregano

parlor palms

peperomia

petunias

polka dot plant

ponytail palm

rosemary (anthos)

snapdragons

spider plant

star jasmine

sunflower

sweetheart hoya

thyme

viburnum

wax plants (hoyas)

white ginger

Looking for more pet-safe plant options? Here are some other, non-toxic houseplants you can try. When in doubt, it’s always a good idea to search the ASPCA database to find the right plant for you and your pets to enjoy safely. WATCH VIDEO

Precautions about pets and plants

While all of the parts of the plants above are regarded as non-toxic if accidentally ingested, individual pets might have specific allergies or sensitivities, so it’s important to observe any changes in your pet’s behavior or health when introducing new plants to your household. Additionally, be cautious of fertilizers and plant food, as they can absolutely be harmful to pets if ingested.

Indoor and outdoor plants that are unsafe for dogs

While there are many pet-friendly plants for green thumbs, the list of poisonous plants is long. Consequences of ingesting one range from mildly irritating symptoms to potential fatality. The list includes trendy plants like Chinese evergreen , sansevieria (also known as mother-in-law’s tongue or snake plant ), golden pothos (also known as devils ivy ), and common yard plants such as azaleas, hydrangeas, and hostas.

Here’s a list of some of the most common plants in and outside your home that pose a risk to your pup:

Most toxic plants for dogs

| Plant | Description |

|---|---|

| Aloe vera | While a useful houseplant, it may induce vomiting, diarrhea, and tremors in dogs and cats. |

| Azaleas and rhododendrons | This family of plants is commonly used in landscaping, but the entire genus of these large flowering shrubs is considered poisonous for dogs. Toxins affect the intestines, cardiovascular, and central nervous system. Eating this shrub can result in vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, and heart problems. |

| Boxwood | Boxwood is often found in wreaths or arches, or as greenery, but ingestion can lead to dehydration, drooling, digestive problems, vomiting, and diarrhea. |

| Chrysanthemum | Though chrysanthemums, nicknamed mums, won’t kill your pet, this plant is a natural insecticide that may result in vomiting, drooling, diarrhea, rashes, and a loss of coordination. |

| Daffodil and jonquil | Daffodils contain tyrosine, a chemical that triggers vomiting. Eating a daffodil can lead to cardiac issues, convulsions, vomiting, diarrhea, heart arrhythmia, and low blood pressure. |

| Dahlia | Dahlias are toxic, though the reason why is unknown. Ingestion can lead to mild gastrointestinal problems and mild dermatitis. |

| Daisy | Daisies are part of the chrysanthemum species so they are also toxic. Ingestion can lead to vomiting, diarrhea, drooling, incoordination, and dermatitis. |

| Foxglove | All parts of the plant are extremely poisonous. Foxgloves contain naturally occurring toxic cardiac glycosides that affect the heart. Ingestion can lead to cardiac arrest and death. |

| Holly | All holly varieties including the popular Christmas holly, Japanese holly, English holly, and American holly, are toxic. Eating holly leaves can result in vomiting, diarrhea, lip smacking, drooling, and gastrointestinal injury. |

| Hosta | Popular because they thrive even with indirect light, hostas can cause stomach upset. |

| Hydrangea | Hydrangeas are poisonous to people and pets in large quantities as there are toxic substances in both the leaves and flowers. Eating this plant can lead to diarrhea, lethargy, vomiting, and more. |

| Iris | These spring blooms add a pop of yellow or blue to your garden, but they add a level of danger for your dog. Eating irises can result in mild to moderate vomiting, skin irritation, drooling, lethargy, and diarrhea. |

| Lantana | This popular, quick-growing ground cover adds a pop of bright yellow, pink, orange, purple, or red to your yard, but in rare cases can cause liver failure in cats and dogs. |

| Lilies | Many lilies, including daylilies and peace lilies, are toxic to dogs and cats. While dogs may experience gastrointestinal upset, the risk is greatest for cats — they’re at risk of acute kidney injury or even death. |

| Peony | This early spring blooming shrub has pink, red, or white flowers, but peonies contain a toxin called paenol that can lead to vomiting, excessive drooling, and diarrhea. |

| Sago palm | All parts of sago palms are poisonous. They contain cycasin, a toxin that causes severe liver damage in dogs. The Pet Poison Hotline reports that severe liver damage can be seen within two to three days of ingestion and the survival rate is 50%. |

| Tulip | The bulbs are the most toxic part of this plant, but every part of these popular spring flowers can hurt your dog. Ingestion can lead to convulsions, cardiac problems, difficulty breathing, gastrointestinal discomfort, and drooling. |

| Wisteria | While beautiful, all parts of wisteria are poisonous — but especially the seeds. The seeds contain both lectin and wisterin glycoside and while ingesting one may not be fatal, as few as five seeds can be fatal to dogs and cats, and even cause illness in children. |

| Yew | All varieties of the yew, a common evergreen, contain toxins that are poisonous to dogs. Every part of the plant is dangerous, as they have taxines, a bitter poison in the leaves and seeds. When ingested by your pooch, it can lead to vomiting, difficulty breathing, seizures, dilated pupils, coma, and even death. |

What to do if your dog has ingested a potentially deadly plant, shrub, or flower

If you think your furry friend has ingested a poisonous plant, call your veterinarian as soon as possible. Delaying a phone call in a potential emergency can cause injury or even death. If you catch your pup munching on one of our aforementioned toxic plants, keep an eye out for symptoms of poisoning.

Dog owners may also call the ASPCA Pet Poison Control Hotline 24 hours at (888) 426-4435 or the Poison Pet Helpline at 855-764-7661 if they suspect plant poisoning.

👉 Check out our comprehensive list of all the foods that are unsafe for your dog to eat, plus pet-safe human foods.

Symptoms of plant poisoning in pets

Symptoms can vary as they are specific to each type of plant eaten. These are the most common symptoms you can watch out for:

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Drooling

- Seizures

- Difficulty breathing

Plant poison prevention

The best cure for poisoning is prevention. Take note of any plants and shrubs in your yard or your house and identify any plants that may be dangerous. Then either remove these plants and shrubs or restrict your dog’s access to them. We’ve also rounded up a list of pet-safe pesticides and pest-control options for your yard and home.

Choosing pet-friendly plants can ensure the well-being of your furry friends while allowing you to enjoy the benefits and beauty of indoor and outdoor flora. Whether it’s the purifying Bamboo Palm or the colorful Snapdragons, incorporating non-toxic plants creates a harmonious environment for everyone in the household. Always research before purchasing a new plant, and monitor your pets for any adverse reactions, ensuring a safe and happy coexistence between pets and plants.

Frequently asked questions

What plants are OK to have around pets?

While many plants might not be an option, you can still have beautiful, colorful plants like snapdragons, marigolds, jasmine, and thyme in your yard and garden.

What is toxic in the garden for dogs?

When it comes to plants in your vegetable garden, there are some plants that you should keep your pup away from. Onions, tomatoes, chives, and garlic can all pose a risk to your dog. Consider fencing these sections in or ensure your dog is supervised at all times. It’s also important to keep dogs away from your compost pile. As foods are broken down, they may become toxic to dogs if ingested — particularly with dairy products and various pieces of bread and grains.

How can I identify toxic plants to keep away from my pets?

Along with this article, there are plenty of great online resources to check which plants you should keep away from your furry friends. You can also consult your local nursery or plant store to see which plants they recommend keeping away from pets. Overall, it’s best to do as much research as you can before introducing a new plant to your home or garden.

What are the early warning signs of plant poisoning in pets?

Symptoms tend to vary by plant, but often the first universal signs are vomiting, upset stomach, diarrhea, excessive salivation, lethargy, skin irritation, and loss of appetite. If your pet is experiencing any of these, contact your vet immediately.

Are there any houseplants that can improve indoor air quality for both humans and pets?

Yes! Plenty of the houseplants listed above provide air-purifying benefits, specifically: Spider plants, Boston ferns, areca palms, and cast iron plants.

© 2023 Betterpet – Advice from veterinarians and actual pet experts

View this email in your browser What to REALLY Know About Chocolate Toxicity for Your PetThe Halloween season can be a great time to enrich your pet with walks and playtime in the falling leaves, bonding with your pet with the increased indoor time, and more. What to REALLY Know About Chocolate Toxicity for Your PetThe Halloween season can be a great time to enrich your pet with walks and playtime in the falling leaves, bonding with your pet with the increased indoor time, and more. At the same time it can be spooky for more reasons than that horror movie your partner is always trying to get you to watch! Pet owners often misunderstand the real dangers that chocolate can pose to their pet. Here are the REAL things you need to know: White chocolate poses no danger (think of a Zero bar). Milk chocolate (Hershey’s), which most Halloween candy consists of, poses a very minor risk. Dark chocolate (baker’s chocolate for example) poses a modest risk. For milk chocolate, a pet has to consume about 3 ounces of milk chocolate per 10 pounds of body weight before even a veterinarian would notice any troubling signs such as excitement (comes from theobromine in chocolate which acts like caffeine). It takes a massive amount of chocolate to be fatal. So to round out with an example, an average 20-pound dog would have to consume two full-sized candy bars (think Snicker’s bars) to even show any clinical signs. A 70-pound Labrador Retriever would have to consume 14 Butterfingers. If your dog eats a piece of chocolate, don’t worry about it, and certainly save yourself a trip to the emergency vet! The worst thing that will happen to your dog is probably digestive upset. However, if your dog is a non-stop eating machine and somehow got into a treasure trove of treats, please seek your veterinarian for treatment. I hope you all have a wonderful Halloween season and I’ll see you in November! Wags, Dr. Marty Becker Want more from Dr. Becker? Read more…Join his Facebook Group! |

Introducing Petfundr!

PetFundr provides crowdfunding for your pet’s urgent, acute or chronic care needs. With PetFundr, you can do it fast, reliably and for FREE!

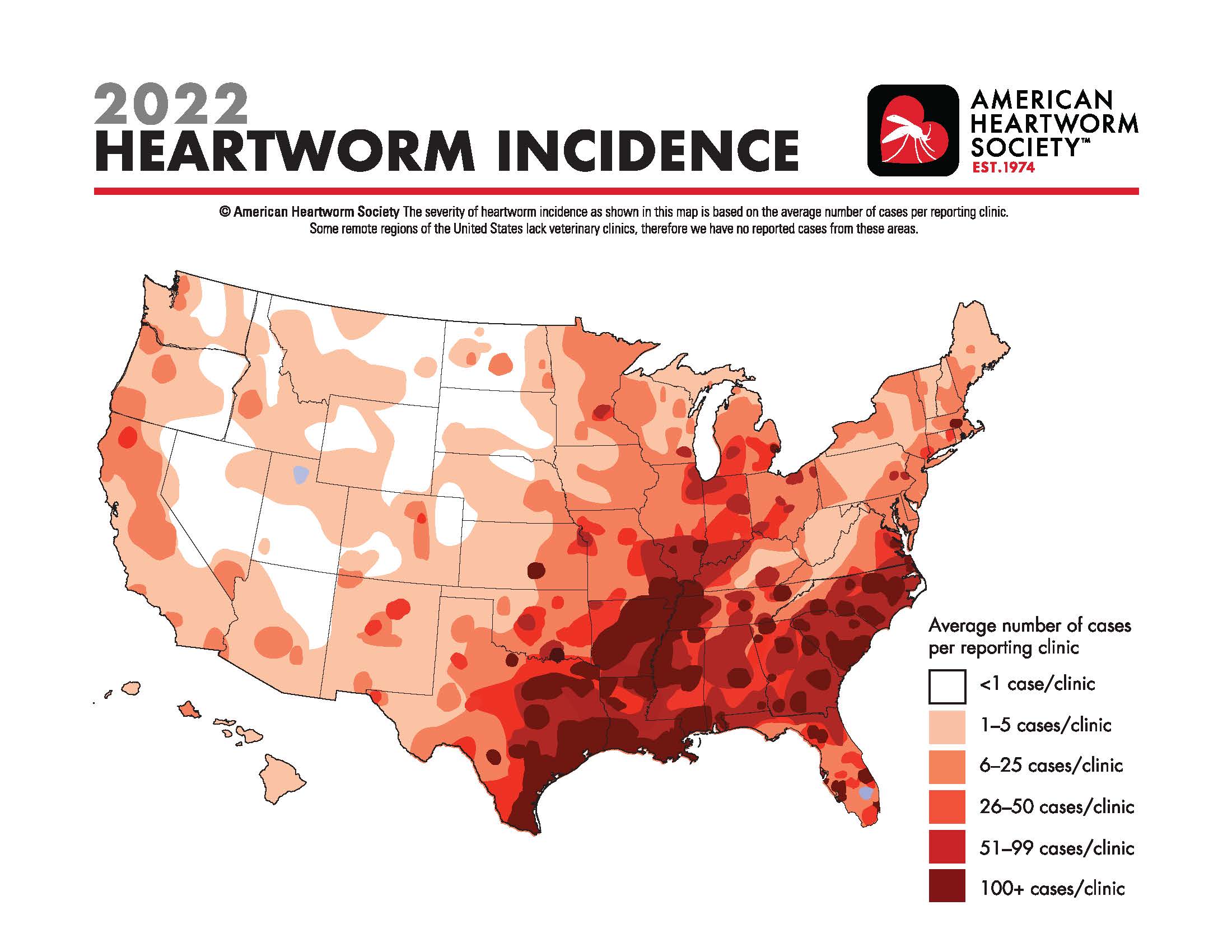

Heartworm Incidence Map

CLICK HERE TO SEE THE MAP at the American Heartworm Society

Catalyzing the field of canine comparative oncology, benefiting researchers far and wide

The Comparative Oncology Program at the National Institutes of Health is celebrating its 20th anniversary of advancing the study of cancer in dogs to help canine and human patients. AVMA News spoke with the founding and current directors of the program and two other veterinarians in the field of canine comparative oncology about their work and the importance of the program. This is the third article in a three-part series.

By Katie Burns

March 20, 2023

The Comparative Oncology Program at the National Institutes of Health has transformed canine comparative oncology since the program’s founding 20 years ago, according to Dr. Deborah W. Knapp at Purdue University and Dr. Steven Dow at Colorado State University, two of many veterinarians working in the field.

Helping pets and people

Dr. Knapp directs the Werling Comparative Oncology Research Center at Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine and serves on the steering committee for the NIH-funded Integrated Canine Data Commons. Purdue’s program in canine comparative oncology was formed back in 1979 and has participated in the Comparative Oncology Program at the NIH since the start.

Dr. Knapp began her career working in a small animal practice, where she observed anti-cancer effects in dogs on piroxicam, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. She studied the topic during her residency in veterinary oncology at Purdue. She later joined the Purdue veterinary faculty, and her research has focused on bladder cancer in dogs—which responds strongly to piroxicam.

Furthermore, bladder cancer in dogs is similar to muscle-invasive bladder cancer in humans. Now piroxicam is widely used in canine oncology, and there have been studies in human medicine of drugs in that class.

“I love the opportunity to help people with their pets when I know how incredibly important that is, and you form those bonds with the owners, and you’re helping their animals,” Dr. Knapp said. “And then at the same time, you’re generating information that can help human cancer patients. And for me, that’s a very special opportunity to have.”

Dr. Knapp said the Comparative Oncology Program at the NIH catalyzed the whole field—giving legitimacy to it, bringing in funding, and coordinating efforts.

Recently, Dr. Knapp and her team finished a study on early detection of bladder cancer in Scottish Terriers, with the results published by Frontiers in Oncology in November 2022. She said, “By the time we see animals with cancer, which is very similar to when physicians see people with cancer, the cancer can be pretty advanced before the diagnosis is even made.”

Scottish Terriers are at high risk of bladder cancer. The team followed 120 dogs that were at least 6 years old at the start of the study, screening them every six months for three years, and found bladder cancer in 32 of the dogs before any outward evidence of cancer. Treatment with deracoxib, another NSAID, was much more effective after finding the cancer early.

Old and new

Dr. Dow, a professor of clinical sciences at Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, got involved with the Comparative Oncology Program at the NIH years ago when CSU was one of the sites running immunological assays in support of several studies through the program’s Comparative Oncology Trials Consortium.

Dr. Dow’s focus is developing immunotherapies for dogs with cancer. He participated in the first round of the PRE-medical Cancer Immunotherapy Network Canine Trials. The NIH funded PRECINCT first in 2017 and again at the end of 2022. Dr. Dow’s laboratory repurposes older drugs designed for other diseases, such as medications for hypertension that have immunological properties that make them promising for cancer treatment.

A recent study out of the laboratory found that using losartan, a medication for hypertension, combined with toceranib, a cancer drug, resulted in tumor stabilization or regression in half of dogs with advanced relapsed metastatic osteosarcoma to the lungs. The results of the osteosarcoma research were published in Clinical Cancer Research in February 2022.

The laboratory also studies other drug combinations that could be used in veterinary clinics now. Dr. Dow said: “These drugs, they’ve been around for a long time. They’re generic, the cost is affordable, and they have good safety margins.”

Malignant gliomas are aggressive brain tumors that share similarities between dogs and humans. A second study from Dr. Dow’s laboratory, published in Cancer Research Communications in December 2022, found that the combination of losartan and propranolol, a beta blocker, along with a cancer vaccine induced durable tumor responses in eight of 10 dogs with gliomas.

Dr. Dow said he thinks the biggest impact of the Comparative Oncology Program over the past two decades has been to increase the visibility of dogs with cancer as a translational model for humans with cancer, benefiting researchers whether or not they work directly with the program.

The role of the program has been not only creating networks, he said, “but also stimulating these interest groups that really begin to think deeply about cancer in dogs and how it applies to similar cancers in humans.”

A dog died after getting bird flu in Canada. Here’s how to keep your pets safe.

See the video here: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2023/04/05/dog-dies-bird-flu-how-to-keep-pets-safe/11607516002/

Adrianna Rodriguez USA TODAY

A pet dog has died after testing positive for the highly contagious bird flu in Ontario, Canada, health officials said this week.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency said the dog tested positive for the virus on Saturday after chewing on a wild goose. The dog subsequently developed clinical signs and died.

While further testing is underway, a necropsy showed its respiratory system may have been compromised by the virus, according to Tuesday’s statement.

Canadian health officials say it’s the first case of its kind reported in the country. The American Veterinary Medical Association says only a few cases of bird flu in cats or dogs have been reported worldwide, with none occurring in the United States.While the U.S. Department of Agriculture hasn’t reported any cases among pets, the agency has found cases in other mammals like skunks, raccoons, mountain lions, bears and foxes. Canadian health officials say it’s the first case of its kind reported in the country. The American Veterinary Medical Association says only a few cases of bird flu in cats or dogs have been reported worldwide, with none occurring in the United States.

While the U.S. Department of Agriculture hasn’t reported any cases among pets, the agency has found cases in other mammals like skunks, raccoons, mountain lions, bears and foxes.

How to keep your pet safe from bird flu

Canadian and U.S. health officials say pets’ risk of contracting and dying from bird flu appears to be very low – but not zero.

Here’s what you can do to keep your pet safe from bird flu:

►Don’t feed pets, including dogs or cats, raw meat from game birds or poultry.

►Keep pets away from dead wild birds found outside.

►Contact a veterinarian if your pet develops symptoms including fever, lethargy, lack of appetite, difficulty breathing, tremors or seizures, or conjunctivitis.