Spot and Tango Dog Food Recall

September 6, 2022 — In a private email to customers, Spot and Tango announced it is recalling four batches of its UnKibble Dog Food product line because samples tested positive for Salmonella bacteria.

What’s Recalled?

The lot codes and SKU numbers for affected products listed below can be found on the bottom and back of each pouch.

No other Spot & Tango products or lot codes are impacted by this recall.

Dog faces can be incredibly cute — here’s how and why

Certain muscles help make dogs ‘smile’ or raise an eyebrow, expressions that help them bond with humans.

From The Washington Post

By Galadriel Watson

August 23, 2022 at 9:15 a.m. EDT

When its owner arrives home, a dog may seem to smile. When a dog wants to go for a walk, it may lift an eyebrow and look pathetic. These adorable expressions have helped create a “deep, long-standing bond between humans and dogs,” says Anne Burrows, a professor of physical therapy at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. They also make dogs unique when compared with species such as wolves or cats.

Burrows and her team discovered that domesticated dogs have a muscle in the eyebrow region that gray wolves don’t: the levator anguli oculi medialis. “This allows dogs to make that puppy-dog-eyes face,” says Burrows. “And wolves just don’t make that face.”

They also studied two muscles around the mouth: the orbicularis oris and the zygomaticus major. Both dogs and wolves do have these muscles. In dogs, however, they’re mostly composed of fast-twitch fibers. In wolves, they’re mostly slow-twitch.

To understand what this means, Burrows says to think of human runners. “If you’re a sprinter, you’re going to run really fast but only for a short distance. Your leg muscles are probably dominated by fast-twitch fibers,” since these can contract quickly.

“If, though, you’re a marathon runner, you might take a while to get up to speed, but you’re going to last a long time. So marathon runners probably have leg muscles that are dominated by slow-twitch fibers.” These shift more gradually into motion but then don’t get tired as soon.

A dog with primarily fast-twitch fibers, therefore, can quickly make facial expressions. (Humans are fast-twitch face-makers, too.) These fibers also mean they’re great at barking, “which is a really fast movement of the lips.”

On the other hand, wolves’ muscles are perfect for extended movements — such as howling. “They kind of turn their mouth into a funnel, and they hold that contraction for, you know, 30 seconds maybe,” Burrows says.

But why are dogs’ and wolves’ muscles and behaviors different? One possibility is that, when humans were first domesticating wolves — which would eventually become what we now know as “dogs” — “they were choosing this animal that barked instead of howled,” Burrows says. Some 40,000 years ago, people were deciding to hang out with dogs that were good at creating alarm calls, such as indicating when a stranger was outside. It just happened to be that these dogs — the ones with more fast-twitch fibers than slow-twitch ones — could also make the sweetest faces.

Then again, maybe those ancient humans felt a stronger bond with dogs that could look cute and the barking trait was a bonus. After all, gazing into a dog’s eyes is known to release a hormone called oxytocin (ox-see-TOH-sin) in both human and dog. “It’s thought to be a love hormone, a hormone that promotes bonding,” Burrows says.

As for pet cats, they have similar facial muscles to dogs but don’t generally use them to peer at us longingly. Instead, they’re mostly used to control their whiskers, which help them navigate their environment. Those movements don’t usually get an emotional response from humans.

“I love my cats,” Burrows says, “but in a different way.”

Gabapentin For Dogs: What You Should Know

Veterinarians are prescribing this medication in record numbers for canine pain and anxiety. Could gabapentin help your dog?

By Eileen Fatcheric, DVM for Whole Dog Journal

Published:March 25, 2021

Gabapentin is a medication that veterinarians are prescribing with increasing frequency, sometimes alone but more commonly in combination with other medications, for the management of pain in dogs. It’s also increasingly prescribed in combination with other medications for canine anxiety. Why has it become so popular? I’ll get to that, but first we have to discuss pain.

TREATMENT OF PAIN IS A MEDICAL PRIORITY

Pain management has become an integral aspect of health care in both human and veterinary medicine. If you’ve ever been hospitalized or had surgery, you will be familiar with the frequent question, “How’s your pain? Rate it on a scale from zero to 10.” So you try to pick a number, again and again, throughout the time you are hospitalized.

It turns out there is a very compelling reason for this. Pain is not our friend. It hurts. But the significance goes much deeper than that. Left uncontrolled, pain causes not only physical damage but also emotional and psychological damage. It delays healing and negatively impacts the immune system. In humans and nonhuman animals alike, it frequently results in harmful, unwanted behaviors like self-trauma, aggression, or withdrawal from the joys of life.

You’ve heard medical professionals say it’s important to stay ahead of the pain. There’s a strong reason for this as well. Untreated pain makes your pain receptors increasingly sensitive, which results in increasingly worsening pain. This is called “wind-up” pain, and it becomes more difficult to control.

We, veterinarians, work hard to prevent pain. When this is not possible, we work even harder to relieve it. This has become easier over the years with the ongoing advancements in science, medical knowledge, and extrapolation from discoveries made in human medicine. Veterinarians now have a whole array of medications and other therapeutics at their disposal for managing pain.

Chronic pain, something that is not expected to go away, is particularly challenging for us. It must be managed, often for the remainder of the dog’s life. For this type of pain, “polypharmacy” (multiple medications) and a multi-modal (more than one treatment modality) approach are usually most effective.

To manage chronic pain, we usually employ prescription medications, as well as safe and potentially effective “nutraceuticals” –nutritional supplements that have positive effects for a medical condition. There are increasing numbers of veterinarians who use Chinese and herbal medicine as complementary therapies to treat pain. Modalities like acupuncture, laser therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, physical therapy, and rehabilitation are all readily available to dog owners in most areas. An increasing number of dog owners now use various forms of cannabidiol (CBD) to treat their dog’s pain.

Pain is a highly personal experience. How one patient perceives pain may be completely different from another. Some have higher tolerances than others. One medication or therapy may work wonders for one patient and do nothing for another. This makes it crucial for owners to be observant, monitor their dogs closely for response to therapy, report accurately back to their veterinarians, and be open to recommended changes in the prescribed pain protocol.

AN UNEXPECTED BENEFIT

Gabapentin has gained popularity in leaps and bounds (hey! that’s what we’re going for: leaping and bounding dogs!) for its potential contribution to pain management in veterinary medicine. But this isn’t what it was initially developed to treat.

Pharmaceutically, gabapentin is classified as an anticonvulsant, or an anti-seizure medication. It works by blocking the transmission of certain signals in the central nervous system that results in seizures. Then researchers learned that some of these same transmitters are involved in the biochemical cascade involved in pain perception, and doctors began exploring its use for pain management.

Today, gabapentin is best known and respected for its ability to manage a specific form of pain called neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain comes from damaged nerves, either deep in the brain and spinal cord or in the peripheral nerves, which are the ones that extend outward from the brain and spinal cord. It is different from the pain that is transmitted along healthy nerves from damaged tissue. Examples of neuropathic pain include neck and back pain from bulging discs, pinched nerves, tumors of a nerve or tumors pressing on nerves; some cancers; and dental pain.

A perfect example of neuropathic pain in humans is fibromyalgia. You’ve probably seen the commercials for Lyrica, a treatment for this chronic, debilitating, painful nerve disorder. Lyrica is pregabalin, an analog of gabapentin. (By the way, pregabalin is used in dogs as well, so if your dog’s current pain protocol includes gabapentin but isn’t working well enough, ask your veterinarian about pregabalin.)

HOW GABAPENTIN IS USED FOR DOGS

Although gabapentin is primarily thought to work best for conditions with neuropathic pain, it is most commonly used as an adjunctive or “add-on” medication in the polypharmacy approach to managing any chronic pain. It is rarely used alone, as the sole medication for pain, even in neuropathic conditions like neck and back pain.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are, and likely always will be, the first-line choice in veterinary pain management. But gabapentin is being added more frequently when an NSAID alone isn’t helping enough. Gabapentin is so safe it can be added to virtually any of the drugs currently used for pain management in dogs. There is a recent study that shows gabapentin has a synergistic effect, which means when it’s used in combination with another drug, such as the opioid pain-reliever tramadol, the effect of both drugs are enhanced.

When adding gabapentin to a current pain protocol, you may see some effect within 24 hours, but you won’t see the maximal effect for seven to 10 days. For this reason, dosage adjustments are usually made only every couple of weeks. Be patient. Gabapentin has the potential to add much value to your dog’s current pain-management plan.

Additionally, adding gabapentin, which has minimal side effects, sometimes allows for dosage reduction of other medications like NSAIDs, which do have potentially dangerous side effects, especially with long-term use. This is a huge plus for both your dog and your veterinarian, who took an oath to “do no harm.”

What are the side effects? Nothing much. There is the potential for mild sedation and muscular weakness, which increases with higher dosages. This side effect is usually minimal at the dosages typically prescribed for pain. Veterinarians actually take advantage of this side effect by using higher dosages of gabapentin in combination with other sedative drugs like trazadone to enhance the calming effect for anxious or aggressive patients in the veterinary clinic setting.

PRECAUTIONS AND SIDE EFFECTS OF GABAPENTIN FOR DOGS

Gabapentin has a huge safety margin in dogs. It won’t hurt your dog’s kidneys or liver and is even safe to use with CBD products, although the mild sedative effect of both products may be enhanced.

There are some important precautions of gabapentin for dogs, however:

- First and foremost, do not use the commercially available liquid form of gabapentin made for humans. This preparation contains xylitol, the sweetener that’s commonly used to sweeten sugar-free gum. Xylitol is extremely toxic, even deadly, for dogs.

- Wait before giving gabapentin after antacids. If you regularly give your dog an antacid like Pepcid or Prilosec, you must wait at least two hours after giving the antacid before giving gabapentin, as the antacid decreases absorption of gabapentin from the stomach.

- Never stop gabapentin cold turkey if your dog has been on it for a while. This could result in rebound pain, which is similar to wind-up pain, in that it’s pain that’s worse than ever. For this reason, always wean your dog off gabapentin gradually.

VETERINARY FAN

As you can probably tell, I am a huge fan of gabapentin for dogs. It helps many of my patients with their pain, it’s safe, and it’s not expensive. I prescribe it most frequently as part of my polypharmacy approach to managing chronically painful conditions like osteoarthritis and cancer. I prescribe it for dental pain. It works wonders for neck and back pain.

While gabapentin is not currently used heavily for post-operative pain as its efficacy in that realm has been questionable, I’m excited right now as there is a study under way to assess its efficacy pre-emptively (before the pain) for dogs undergoing surgery. Many veterinarians already prescribe it for their surgical patients to be started before the procedure, because they have so much faith in it.

Gabapentin is extremely safe for dogs, and it has the potential to alleviate pain for our dogs and improve their quality and enjoyment of life. If you’ve been wondering why so many veterinarians are prescribing this medication more and more, there’s your answer. We see results, plain and simple.

Gabapentin for Anxiety

Gabapentin does not have a direct anxiolytic (anti-anxiety) effect, limiting its usefulness for treating the chronically stressed, anxious dog as a stand-alone drug. However, as with its synergistic use alongside pain medications, it is sometimes prescribed in combination with Prozac (fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reputable inhibitor [SSRI]) or Clomicalm (clomipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant [TCA]) for persistent cases of generalized anxiety, panic disorders, compulsive disorders, and true separation anxiety.

The goal when adding gabapentin in these instances is to help the dog relax in the face of his stressors, as you try to help him through his issues with appropriate desensitization and behavior modification exercises. This is particularly useful in cases where the dog is already receiving the maximum dose of anti-anxiety medication, with less than the desired effect.

It’s important to note that medication alone is not likely to relieve anxiety for your dog unless paired with the above-mentioned desensitization and behavior-modification exercises. These exercises can be prescribed by your veterinarian or a veterinary behavior specialist.

Gabapentin’s sedative effect at higher dosages can be used on an as needed basis to help dogs relax and get through specific situations that cause undue stress for them. Examples of this type of situational anxiety are veterinary visits, grooming appointments, long car rides, thunderstorms and fireworks.

3 Signs Your Dog Is Stressed

From UC Davis Magazine

by Shelby Dioum | Jul 6, 2022 | Aggie Life, Animal Science, Spring/Summer 2022

Dogs get stressed just like humans. When dogs act out, tense up or become distant, their owners may wish that their dogs could verbally tell them what’s wrong. Fortunately, though, dogs have body language that can help their caregivers better understand them. Emma Grigg, an animal behaviorist at UC Davis, said that understanding their behavior plays a significant role in their welfare. “It makes us more compassionate when they’re doing something we don’t like if we can understand what’s triggering that behavior,” Grigg said. Here are some ways that your dog may express to you that they are stressed or anxious.

Leaning away

This is a sign that a dog is fearful of a certain situation. Some dogs will lean away from what is stressing them out (an unwanted hug, for example). Other times, a dog may avert its head slightly, but keep its eyes fixated on a person or thing. According to Grigg, dogs may do this to pretend that whatever is stressing them is not there, or to signal that they don’t want an interaction to continue.

Tensing up

“When [dogs] suddenly get very still and tense, it’s a huge sign that they’re uncomfortable,” said Grigg. Many dog owners may think that a tense dog is being stubborn or dramatic, but they may actually be anxious or irritated. Relaxed dogs are wiggly and loose, according to Grigg, so a dog may be very uncomfortable if it suddenly goes tense.

Firmly closing the mouth

“A happy dog will have a relaxed, open mouth with their tongue hanging out,” said Grigg. On the other hand, a dog with a firmly closed mouth may be uncomfortable in a particular moment or environment. “This sign is subtle and can be easy to overlook,” Grigg added.

Homemade Frozen Dog Treats

From Whole Dog Journal

By CJ Puotinen

Published:June 21, 2022Updated:June 30, 2022

If your dog is too hot this summer, cool her off and make her happy with healthy homemade frozen dog treats like “pupsicles”!

Our dogs are just as fond of ice cream, popsicles, and other frozen treats as we are. But frozen treats, including those sold for pets, can be high in sugar, difficult to digest, expensive, or contain artificial flavors, colors, and even potentially dangerous ingredients.

Fortunately, it’s easy to save money, add variety, improve the nutritional content of your dog’s treats, and help your hot dog cool down as temperatures climb with these homemade frozen dog treats.

How to Make The Best Frozen Dog Treats in Town

Ingredients: Avoid ingredients that are harmful to dogs, such as the sweetener xylitol, macadamia nuts, grapes, raisins, onions, and chocolate. Prevent unwanted weight gain by limiting fruits, fruit juices, and other sources of sugar, and feed all “extra” treats in moderation.

Many dogs are lactose-intolerant, which can make regular ice cream and frozen milk products indigestible. Substituting fermented dairy products like yogurt or kefir, or using unsweetened coconut milk, which is lactose-free, helps dogs avoid digestive problems.

Equipment: Recommended equipment includes a sharp knife and cutting board, blender or food processor, and something to hold and shape treats during freezing, such as simple ice cube trays, sturdy rubber chew toys, popsicle molds, paper cups, silicone molds, wooden strips, and edible sticks.

Storage: Once treats are frozen, place them in air-tight freezer containers or zip-lock bags for freezer storage. This prevents sublimation, during which frozen foods dehydrate, and it prevents the transmission of odors to and from other foods.

Frozen Dog Treat Disclaimer: If your dog loves to chew ice cubes, she’s not alone – but ice cubes are potentially hazardous. According to Tennessee pet dentist Barden Greenfield, DVM, “Dogs have a tendency to chew too hard and the force of breaking ice is substantial. This leads to a slab fracture (broken tooth) of the upper 4th premolar, which many times exposes the pulp, leading to tremendous oral pain and discomfort. Treatment options are root canal therapy or surgical removal.”

The risk of breaking a tooth increases with the size of frozen cubes, so avoid this problem by freezing small cubes, offer shaved ice instead of cubes, or add ingredients that produce softer cubes, such as those described here. Small amounts of honey, which can have health benefits for dogs, help prevent a “too hard” freeze.

Use whatever safe ingredients you have on hand, and experiment with quantities. There is no single “right” way to make a frozen treat that your dog will relish. An easy way to predict whether your dog will enjoy a frozen treat is to offer a taste (such as a teaspoon) before freezing. If your dog loves it, perfect. If not, add a more interesting bonus ingredient.

Simple Frozen Kong Ideas for Easy Frozen Dog Treats

Nothing could be easier than filling a sturdy dishwasher-safe, nontoxic, hollow, hard rubber toy such as a Classic Kong with any of the following ingredients before leaving it in the freezer. Block any extra holes to prevent leakage, leaving one large hole open for filling. Popular dog-safe ingredient options include:

- Mashed ripe banana

- Pureed soft fruit or vegetables (remove seeds or pits before blending)

- Canned dog food

- Nut butter (look for sugar-free peanut butter or other nut butters that do not contain xylitol)

- Diced apple

- Chopped or shredded carrots

- Shredded unsweetened coconut

- Plain unsweetened yogurt or kefir

- Dog treats

Combine your dog’s favorite ingredients and fill the hollow toy. If desired, seal the top with a layer of peanut butter, squeeze cheese, or a dog treat paste such as Kong’s Stuffin’ Paste. Store the toy so its contents remain in place while freezing. For storage, keep frozen Kongs in a sealed freezer container or zip-lock bag.

Another simple summer treat is a few chunks of frozen dog-safe fruits or vegetables delivered by hand or in a small bowl, such as banana, apple, peach, watermelon, cantaloupe, honeydew melon, or green beans.

Dogs and Petting

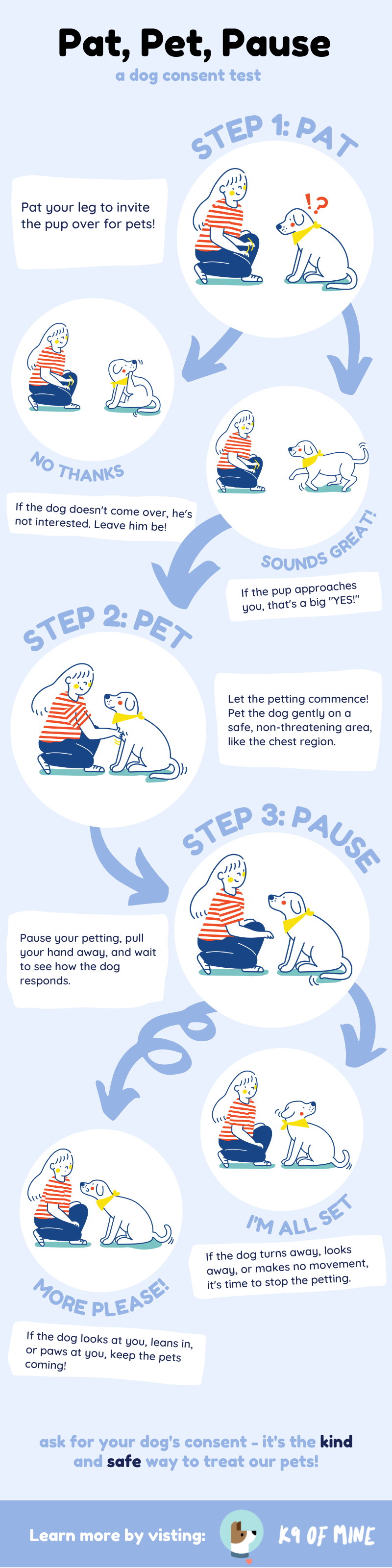

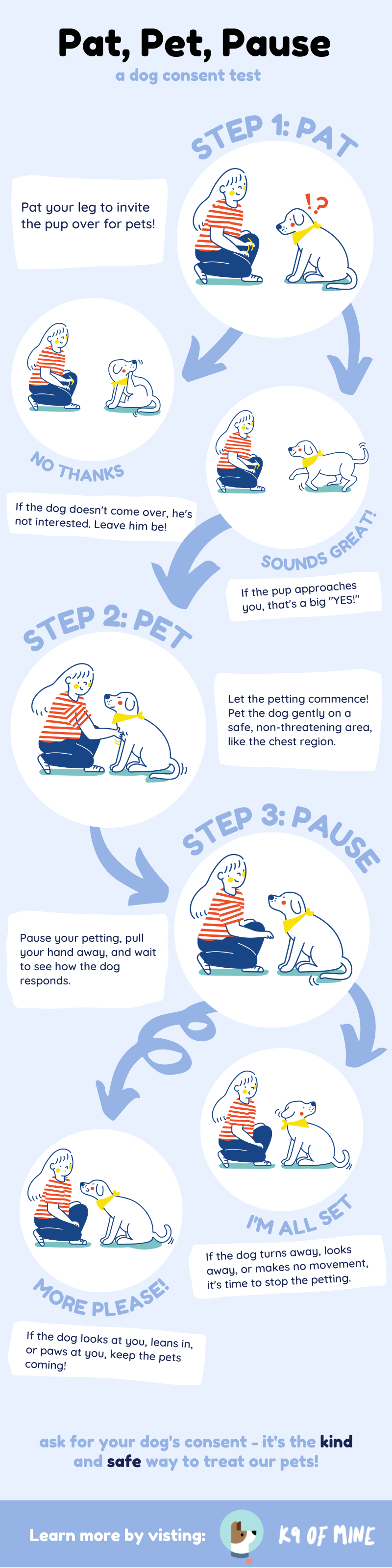

Sometimes it can be difficult to know when our pets are interested in a physical interaction with us. Not all dogs want to be cuddled all the time! To help owners better assess their dog’s emotional state, K9 of Mine has created a new infographic as part of their Dog Consent guide. The Pet, Pat, Pause technique was originally developed by Justine Schuurmans of The Family Dog. In each stage of interacting with a dog, this exercise always gives the dog a choice and allows them to say “no thanks” when they’re feeling hesitant or unsure!

Dogs and Petting

Behavioral Effects of a Companion Dog Loss on a Cohabiting Companion Dog

Dr. Jean Dodds

April 1, 2022 / General Health / By Hemopet

Many of us who have two or more companion dogs will notice behavioral changes that we perceive as grief-related if one of the pets is very ill or dies. As fellow pet parents, we know this to be true and have our own personal anecdotal stories.

For researchers, anecdotal beliefs or reports are problematic. They recognize that pet parents may be projecting their feelings of grief onto the companion dog. Confounding the matter are factors that may change such as household dynamics, pet parent behavior, or habits that may impact the surviving dog’s behavior.

Researchers have observed mourning habits and rituals of many species such as dolphins, elephants and primates in the wild. In those circumstances, researchers are simply observing and are usually devoid of a personal attachment. True, they could form an emotional bond and project some bias, but they are not interacting or affecting the outcome. Another factor that compounds the issue is that behavioral responses to death have rarely been observed in wild or feral dogs.

A great basic survey that quantified behavioral changes in companion pets was completed in 2016 by Jessica Walker, Natalie Waran and Clive Phillips in Australia and New Zealand titled, “Owners’ Perceptions of Their Animal’s Behavioural Response to the Loss of an Animal Companion”. We encourage you to read it.

A couple of years later, researchers having different specialties published a questionnaire directed at Italian dog owners who had lost at least one companion dog from a minimum of a two-companion dog household. They then applied various methodological scales to analyze the responses not only for pet humanization but also for pet bereavement for another pet. Eventually, they published a paper called, “Pet Humanisation and Related Grief: Development and Validation of a Structured Questionnaire Instrument to Evaluate Grief in People Who Have Lost a Companion Dog.”

With this foundation, the team was able to expand and complete another study: “Domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) grieve over the loss of a conspecific”. This study gets really interesting because it provided comparisons based upon the type of bond two companion dogs may have. They asked if the cohabiting companion dogs were friendly, agonistic, mutually tolerant, parentally based (meaning parent-offspring) on both owner observation and the genetic association towards one another. They also inquired about the activities or areas the two dogs might have done together such as sleeping together, playing, sharing food, and grooming. Then, the observed behavioral changes such as playing, sleeping, eating, fear, vocalization, elimination, attention seeking, and level of activity, once one dog might have passed on.

They found out that a friendly and parental relationship between the two dogs was associated with stronger behavioral changes, while no association was found between behavioral variables and an agonistic/mutual tolerance relationship.

The Problem with, “May I Pet Your Dog?”

From: Whole Dog Journal

www.wholedogjournal.org

Let’s ask the dog – not the handler – and learn when his body language truly is answering “Yes!”

By

Published:May 23, 2022

It used to be that if folks wanted to pet your dog, they just reached out and did it. Happily, in today’s more well-informed world, there’s usually a quick, “May I pet your dog?” first. All too often, though, the moment that permission is granted, the stranger is moving in close and looming over the dog, swiftly thrusting a hand an inch from the dog’s nose. The dog – perhaps pushed forward a bit by the owner who sees how eagerly the other human wants this – might find an enthusiastic, two-handed ear jostle is next.

For some dogs – the stereo-typical Golden Retriever, perhaps? – this is the moment they’ve been waiting for! That extra human attention may even be the highlight of their walk. If your family has only included extroverted canine ambassadors like this, the idea that a dog would not welcome an outstretched hand is incomprehensible.

Yet, comprehend we must. Because, believe it or not, few dogs automatically love being trapped on a leash and touched by new people. As hard as it is for us to accept, that quiet dog being petted may well be hating every moment that the human is enjoying so much. While that’s important to understand when you’re the stranger in the scenario, it’s absolutely critical when you’re the one holding the leash.

DON’T ASSUME THAT DOGS WANT TO BE PETTED

Indeed, plenty of wonderful dogs are not eager to say hello to strangers. They may feel anything from uninterested, to wary, to terrified. In some cases, they have been specially bred – by humans – to feel what they’re feeling.

Unfortunately, because we humans value petting dogs so much, we often ignore that pesky truth. We tend to believe that all good dogs should happily accept petting from anybody at any time. But dogs have plenty of reasons for choosing to say no:

- Perhaps they’ve been bred to guard, so this forced interaction with strangers is deeply conflicting.

- Perhaps they’re simply more introverted and don’t enjoy this kind of socialization.

- Perhaps something in their background has made them less trusting of people.

- Perhaps normally they’d be all in, but today their ear hurts, or they are very distracted by the big German Shepherd staring at them from across the street.

There are many reasons, all legitimate, that may make a dog prefer to skip this unnecessary interaction.

DON’T GIVE CONSENT ON BEHALF OF YOUR DOG

Becoming conscious of just how deeply some dogs do not want to be randomly touched is the first step toward realizing that we really should be asking dogs, not their handlers, whether or not we can pet them. Ultimately, it’s the dog’s consent we need in order to safely pet them, not the human’s.

Maybe the idea of giving our dogs the right to consent feels strange to you. For my part, it feels downright creepy to not give my dog the right to consent or decline to being touched by a stranger. It feels wrong that I have the power to decree, “Sure, absolutely, you go right ahead and put your hands all over this dog’s body. She’s so pretty, isn’t she? We all love to touch her.” Ew!

Of course, dogs can’t verbally answer the “May I pet you?” question (when given the opportunity to do so), but they sure do answer with their body language. Unfortunately, most people don’t have the skills to read what can be very subtle signals, and as a result, many dogs are routinely subjected to handling that makes them uncomfortable. Worse, this often happens while they’re restrained by a leash with their owner allowing it.

That experience can make dogs even less enamored of strangers, and – the saddest part – less trusting of their owners, who did not step up to help them through that moment.

TIPS FOR MAKING FRIENDS WITH A DOG

I give my dogs agency when it comes to who touches them and when. If somebody asks, “May I pet your dog?” I smile at their interest and tell them I’d love for them to ask the dog. Then I show them how:

- Keep a little distance at first.

- Turn a bit to the side, so you don’t appear confrontational.

- Use your warm, friendly voice to continually reassure.

- Crouch down, so that you’re not looming in a scary way.

- Keep your glances soft and light instead of giving a steady stare.

- Offer your hand to sniff. But instead of the fist shoved unavoidably in the dog’s face (which is what society has been taught is the polite thing to do), simply move that hand ever so slightly toward the dog so she has a choice of whether to get closer to investigate. Look elsewhere as she does so, so she can have a little privacy as she sniffs.

Often, this approach gets us to a waggy “yes” from even a shy dog in 30 seconds!

HOW TO TELL IF YOUR DOG IS GIVING CONSENT

If the dog pulls toward the stranger with a loose, relaxed, or wiggly body, the dog is saying yes. Great! The next step is to begin petting the dog in the spot she’s offering – likely her chest or rump. (A top-of-the-head pat is on many dogs’ list of “Top 10 Things I Hate About Humans.”)

If my dog does not give a quick or easy “yes,” I may try backing us up a bit and making conversation, because many dogs warm up after having a few minutes at a safe distance to size up a new human. I might feed my dog a few treats while talking to the stranger, or give him some treats to toss near my dog. If she then relaxes and leans into the experience, great!

If not, we just call it a day and move along. That is also – and this is critically important – great! No harm, no foul. No need to apologize if our dogs say, “No thanks.” We can simply and cheerily head on our way.

Dog Stress Signs You Should Know

From Calmingdog.com

OCTOBER 26, 2021 https://calmingdog.com/blogs/main/dog-stress-signs-you-should-know

Many times, we try to guess what our dogs are thinking and how they might be feeling. As a dog owner, how often have you just sat to the side and watched your dog do his dog things, living in his dog world? Do you wonder what it’s like to be a dog and what dog stress is?

We sit down and watch our dogs and wonder what they think because we don’t know. We cannot say one hundred percent, for sure, what our dogs are feeling. We cannot because they are animals, and we are humans. They cannot talk to us and let us know how they are feeling.

We can try to guess sometimes. We look at their faces and body language and try to judge for ourselves how they feel. However, it is still tricky to do because sometimes, a dog can be confusing. Ever see a dog yawn? Well, a dog’s yawn can mean different things. It can mean tiredness or indifference or stress, or it could just be because you or another dog yawned. Something like this that can mean different things is sometimes complicated to judge, or maybe your dog is experiencing stressful situations.

But sometimes, you can tell exactly what a dog is feeling and know when he is feeling a particular emotion because it is just so clear. One of such clear, unequivocal emotions is stress. Some things your dog does or some ways he acts that let you know that he is stressed.

Are you ready? Then let’s dive in! In this detailed article, we will talk about what causes stress in dogs, those cues that tell you when your dog is stressed; and give you pointers on what you should do about them. Just click the link below:

https://calmingdog.com/blogs/main/dog-stress-signs-you-should-know